“The Mythos of My Life”

A desperate darkness fell over the now-familiar confines of my new apartment when I confirmed that a single, small photo-card was nowhere to be found among my possessions OR at my brother, Chris’ house (where I’d decamped for a few months).

Imagining that I’d secured it away somewhere, I texted to ask if he would take one more look, stating, “ The whole mythos of my life is wrapped up in that picture… it’s hard to explain.” But having found it a day later among a bunch of files—its thick acrylic frame innocently rendering it invisible when viewed from above—I am compelled to try to.

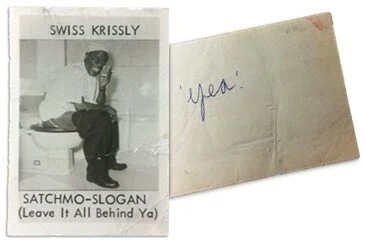

The front and back of Louis Armstrong’s “calling card.”

Our attachment to objects, notes Bill Shapiro (author of “What We Keep”), goes back to the Neanderthals “[sitting] around this mind-blowing thing called fire and [asking] each other what they’d drag away should the cave alight.” So weighted with associations was my found item, you’d think it impossible to drag. In reality, it’s nothing more than a creased and careworn 3” X 4” card promoting the laxative, Swiss Krissly. On the front, a smiling Louis Armstrong sits on the toilet, with the words “Leave it all behind ya” (“Satchmo’s Slogan”) along the bottom. On the back, the single word, “yea” is casually written in blue ink.

Armstrong regularly handed out the photo—attributing his loss of 150 lbs. to the product to anyone within earshot. "I take my Swiss Kriss, man, they keep you rollin',” he said. “Old Methuselah, he'd have been here with us if he had known about them."

The story goes that my father, who had an office in Chicago, met Armstrong after a late-night performance (probably at the famed Mister Kelly’s) and so engaged him with his encyclopedic knowledge of Armstrong’s music (if not his wide-eyed fandom), that the two ended up talking ‘til dawn in the back of Armstrong’s limousine (where he gave my father the card).

My teenage tribute to “Satchmo” (which hung in my father’s home until his death)

The card’s invitation to “leave it all behind me” is especially ironic, considering all that I will forever associate with it. Its hold on me is equal parts mythos and memory. The sound of my brother mimicking Armstrong and Jack Teagarden singing, “Rockin’ Chair.” The memories of being awakened Sunday mornings by my father at his Slingerland drum set, joyfully playing along to Armstrong’s Hot Five (or Krupa’s “Drum Boogie”). Armstrong was my first literary fixation—the legend of his birth on July 4th, 1900 calling to me from numerous books (though it was later proven to be August 4th, 1901). And he was the subject of one of my first teenage paintings (shown)—the ochre strokes coursing around him just as my father’s love of jazz still courses through me.

Picturing them winding through Chicago’s streets in the wee hours, I think how far each had come. Armstrong: jazz’s global ambassador and its most celebrated artist—born into dire poverty in New Orleans and sent to its Colored Waifs Home as a juvenile delinquent, where he learned to play cornet, before finding fame in 1922 with King Oliver’s band in that same windy city. My Philly-born father: the depression-era—and only—child of an overly-protective, pious mother, who would go on to get his Masters in Philosophy at Columbia, create the discipline of Construction Management (with offices from San Paulo to Saudi Arabia), and be named to Nixon’s Enemies List and the board of the American Symphony.

Armstrong was nearing seventy. My father was not yet forty. By my estimation, their meeting roughly coincided with the1969 release of “Hello Dolly” (its scene with Armstrong always leaves me teary, as his wave goodbye to Streisand seems to hint at his death a year and half later). Only five or six at the time, I would be gifted the photo many years later. But I’d like to think that I sensed then what I know to be an unquestionable truth now (and one the card represents): My father’s complete lack of prejudice—towards men and music.

Armstrong’s cameo in 1969’s “Hello Dolly!”

There’s been much talk lately suggesting that ALL white people are inherently racist… that to exist in a world defined by white privilege automatically deems us so. And it continues to make me bristle slightly—especially when considering my father.

He was not at all what is now termed a performative ally (those who do little more than flaunt their afro-centric tees and hashtags). Nor was he someone who placed the burden of racial awareness education on black friends or coworkers. He was a voracious reader of everyone from Baldwin to Barack, who produced August Wilson’s “The Piano Lesson” when on the board of a local Harrisburg theater company. (The boxed collection of Wilson’s plays gifted to him by the cast now sits on my bookshelf.) He hired black people…and gay people and deaf people (with one deaf employee becoming the subject of a 1970’s New York Times article). He was a private man who could list his important, life-affirming friends on one hand—and counted two black men among them.

Like Armstrong’s photo, I hope the images of Lena Horne, Duke Ellington, Billy Strayhorn and vaudevillian Bert Williams that adorn my walls are seen for what they are. Evidence of a familial disposition to both celebrate and learn from those outside and different from ourselves. Where others see a disposable (if not embarrassing) promotional item, I see the symbol of a profound inheritance.

It is the talisman of a father who showed his children how to live without prejudice (AND that you must act against it).

It is the token of a man who lived his life to music—and asked that it be celebrated with a band marching through his memorial service playing the Armstrong classic, “When the Saints Go Marching In.”

It is the tale of two men immune to the distraction of race—in a city and time ignited by it—when united by their shared love of music.

It is everything to me.